I read an interesting article on the New York Times “Well” blog about “How meditation changes the brain and body” It discussed a study published in Biological Psychiatry Journal which was conducted on 35 unemployed men and women who were experiencing considerable stress during their job search.

Dr. David Creswell, an associate professor of psychology at Carnegie Mellon University who conducted the study, said half the subjects were taught formal mindfulness meditation at a residential retreat center; while the rest completed a kind of sham mindfulness meditation that was focused on relaxation and distracting oneself from worries and stress.

At one point in the study they had everyone do stretching exercises. The difference was that mindfulness group paid close attention to bodily sensations, including unpleasant ones, whereas the relaxation group was encouraged to chatter and ignore their bodies, while their leader cracked jokes.

After three days of studying the 35 participants, they found that everyone reported that they generally felt better and less stressed, but when they did brain scans on them, they found that the ones who had been taught the genuine mindfulness meditation techniques exhibited more activity in the areas of the brain that process focus and calm. Four months later those who had practiced the genuine mindfulness meditation showed much lower levels in their blood of a marker of unhealthy inflammation. Dr. Creswell believes that the changes in the brain led to the subsequent reduction in inflammation but he and his colleagues couldn’t determine why that was.

It is a good thing to be mindful, in other words to be present in the moment as we engage in our daily activities. Yet while scientific studies that demonstrate the benefits of meditation can be helpful in convincing skeptics, there is often a very important understanding missing from what is commonly taught as mindfulness. And that is the appreciation of who is the perceiver. In other words, who it is that is experiencing stress, perceiving the mind, and is desiring to be mindful.

Empirical scientists tend to conclude that if they can’t observe something with their senses, it does not exist. So they reduce all phenomena to the actions and reactions of atoms, molecules, and cells. In other words, they have concluded that everything has a chemical origin. So they are unable to recognize the existence of the mind as a separate and distinct from the brain. When in fact, the mind is a subtle material energy which cannot be perceived by the senses, no matter how powerful a microscope one may have.

From the ancient Vedic scriptures, the source of yoga wisdom, there is a clear distinction made between the brain, the mind, and the perceiver of both. It is, of course, undeniable that the mind affects the brain and that the brain affects the mind. But to fully understand the interaction between the two, we need to understand their true nature, function, and how they relate to the individual living being.

The Bhagavad-gita teaches that material nature manifests itself as both gross physical and subtle energies. The atoms, molecules, and cells that make up the human body are gross physical energy, by which we mean they can be observed by the senses. But the conscious individual being, experienced by each and every one of us as “I,” is actually spiritual in nature. This spirit soul is eternal and does not die when the body dies. It is the source of consciousness, feeling, and will. While neither the mind nor the spirit soul can be observed as having a chemical origin, their presence can be perceived once we come to understand Aham Brahmasmi, that I am an eternal living being. This is such an important point, and it is a world-view that is rarely discussed. However, as I will touch upon in future posts, it’s a world-view that offers so many solutions to the problems we face as individuals and as a society. If we are mindful of our actual true nature and spiritual existence, we will truly experience the relief from stress and anxieties that we all seek.

Wishing you well,

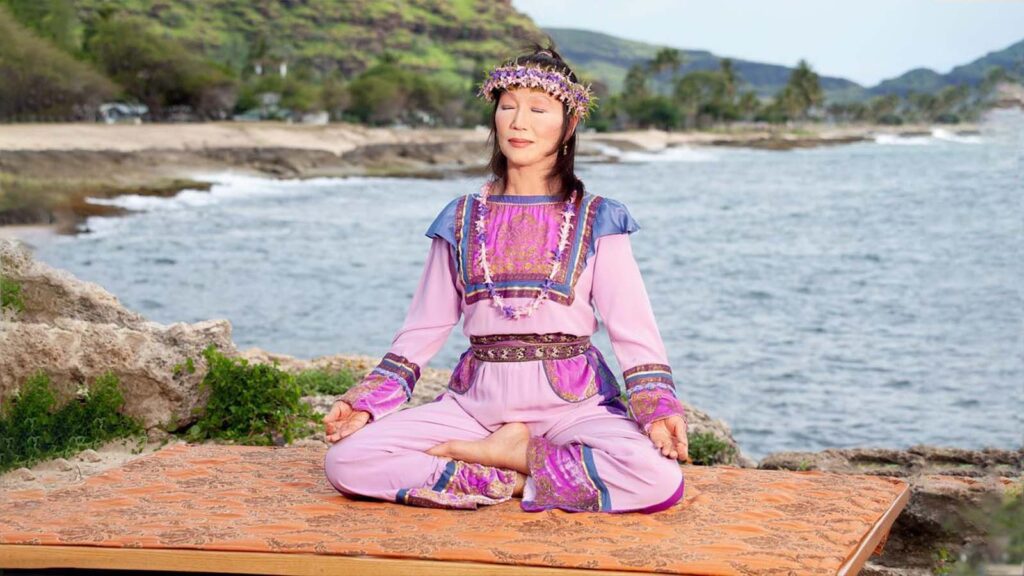

Wai Lana